-

I was born in St Ives, Cornwall in 1951, one of six. My father was Peter Lanyon - a landscape painter who became a major figure in the world of art.

After the war St Ives had become a centre of the modern movement in abstract art and my father was commissioned to produce the painting Porthleven for The Festival of Britain. His mentors were Naum Gabo and Ben Nicholson. While I was tearing round the garden as Davy Crockett, movers and shakers of art were passing the sugar and spreading the cream.

Shortly before he died in 1964, as the result of a gliding accident, we spent some days together in his studio making a model aircraft. We made prototype wings out of polystyrene and tried to strengthen them with muslin and glue-size. Years later I read what someone had written about his painting Clevedon Night, which had these two prototype wings attached to the canvas. They might be 'boats bobbing up and down' but I knew what they were. They weren't boats. But it doesn't matter whether this was true or not. That isn't the point - we read our own life into paintings.

A few days with him in the studio, a few days camping out in the Thames van on Perranporth Airfield and he was gone. I was thirteen. He was forty-six. His death came into me like an ocean.

I was brought back from Bryanston to the local grammar school in Penzance. I won the art prize and thought about going on to art school but my mother said, 'You'll end up in a corner screaming.' This was the 1960's. In the 30's she'd had to do three years of drawing before they'd let her hold a brush. So that was that. It would be twenty-five years before I got the smell of paint again. I went on to university and joined the meritocracy - the beginning of the great unwinding of the class system. It was exciting. There was a political edge - we were on the streets.

Half a century later, I look back in wonder:

Upper class background, middle class education, university career in free-fall - I should have been a class disaster. The one saving grace in messing up is you get a new beginning. If you can realise that and shoulder the weight of having taken goodwill from others and shagged it you get a new beginning.It was a terrible trade off but I got so much from four years at university starting with Geology and Psychology. In my last year I read History of Science, Archaeology and Linguistics. I was a burning fuse - changing courses and reading stuff that wasn't part of the brief. I was after something.

Four years in academia then a job on a tractor - working in the building trade, becoming physical. The tragedy and sadness of my loss was bearable. I trained as a carpenter and joiner. I handled many diverse materials - renovating four houses, subcontracting and working for other builders. I just learned so much.

It was not until 1988 that I began to take my artwork seriously. At that time I was drawing and painting every morning with my son, in the days before he went to school. He always had the best titles. I'd ask him about one of his drawings and he'd say with the absolute sincerity of a four-year-old, 'Three Cows Walking on the Water'.

Between my father and my son I had begun to address the problem of what anything is, or is meant to be in a painting. If cows could walk on water and bits of polystyrene that were once wings can bob up and down like boats, then painting is alive and the better for being marginalised by all the exquisite distractions of sound and movement.

As a small child growing up in St Ives there's something about the way the sea is up there. There's a high horizon - Godrevy Lighthouse and the headland. There's this enormous bay. You're high up looking down over the harbour. Then you're down in through the houses and the sea is way up there. So you've always got this sense of going right down into and being held in this valley.

But what's happening with the sea? If you go out to the horizon in your imagination, where is it going left? The sun comes up here behind you and goes down over there. The sun is always going down to this mysterious place - it's actually Labrador. The fishing boats went out there and came back. You go out to Seal Island and you get a bit of it: Suddenly you're down in the swell of the ocean or over the top of it and the cliffs are black.

That sense of where you are in your childhood's headspace: In your left hand it's over there where the sun sets. When you look back you map on your body your life's journey. The way the map is constructed, even the way we see the earth is literally a construction. When you take it apart it's just history but your own journey is unique. That's the special thing when you begin to draw and paint your life in your work.

If you come here you dream of living here or coming back. If you come here as a child you never forget. If you've grown up here you have to deal with the problems thrown up with the effects of tourism as an industry - a disneyfication, a picturesque, a cheapening of values and a false glorification of its wonderfulness.

You can't escape. Oxygen is being pumped into just about everything that can make a buck for good reason. Cornwall has always been exploited and the people who live here the most exploited. The people of this place are scattered to the ends of this earth - most of them.

-

1994: Rainyday Gallery, Penzance

1996: Salthouse Gallery, St Ives

2000: Rainyday Gallery, Penzance

2001: Rainyday Gallery, Penzance - solo

2001: Wiseman Originals, London

2001: Affordable Art Fair, London

2002: Badcocks Gallery, Newlyn - solo

2002: Affordable Art Fair

2003: Rainyday Gallery, Penzance - solo

www.bbc.co.uk/cornwall/art/2003_stories/matthew_lanyon.shtml

2004: The John Davies Gallery, Stow-on-the-Wold

Wiseman Originals, London

Rainyday Gallery, Penzance - solo

The Hutson Gallery, London

Platform 100 Exhibition, London

2005: Wiseman Originals, London

Rainyday Gallery, Penzance - solo

Minster Fine Art, York - solo

2006: Minster Fine Art - Solo

New Grafton Gallery

The Rainy Day Gallery - solo

The John Davies Gallery

2007: Tate St. Ives

Rainyday Gallery - solo

Porthminster Gallery

The John Davies Gallery

2008: Porthminster Gallery - summer collection

Rainyday Gallery - solo

2009: Porthminster Gallery – mixed

Rainyday Gallery – solo

Tutti arts gallery – mixed

Bohun Gallery – mixed

2010: Porthminster Gallery – mixed

Rainyday Gallery – solo

Gloss Gallery – mixed

New Craftsman Gallery – two man

2011: Bohun Gallery - mixed

Porthminster Gallery – mixed

Open Space Gallery – mixed

New Craftsman Gallery – solo

Wetpaint Gallery – mixed

2012: 18/21 Gallery - mixed

Porthminster Gallery – mixed

Open Space Gallery - mixed

New Craftsman Gallery – solo

Hilton Fine Art – mixed

2013: Porthminster Gallery – mixed

Porthminster Gallery – solo

2014: Porthminster Gallery – mixed

New Craftsman Gallery – solo

2015: Porthminster Gallery – solo

2016: Falmouth City Art Gallery – mixed

New Craftsman Gallery – solo

2017: Uillinn, West Meets West, West Cork Arts Centre, three man show

2018: Faster than Words, Older than Thought; New Craftsman Gallery St Ives, solo

2024: No Holds Barred: Life and Art, New Craftsman Gallery

-

Text written by Judith Lanyon in 2014, images in collaboration with Matthew Lanyon; lines in italics

are quotes drawn from his own letters/writing about paintings and poems.1951 Born St Ives, Cornwall to Sheila and Peter Lanyon, third child of six.

1956 Moved to Little Park Owles in Carbis Bay.

1959 Matthew’s mother gave him the Iliad to take away to private school in Dorset when he was 8. He persisted in trying to understand and discover what he was meant to find there but felt that he was continually failing, that some essential significance of Greek mythology remained locked up in the stories. His persistence was to become as significant and integral to his development however as the mythology:inside the bull, a god

inside the image of a bull, a girl

inside the girl, half man, half animal

the MinotaurRuled by a precarious indifference to the divine, we moderns simply re-invent it in the perfection of our own images. But so as not to be ruled, and to avoid making a fetish of them, we climb inside our own clay, there to construct an armature – both support for, and abstract form of the image.

1964 In the summer holidays that year Matthew spent a week alone with his father for the first time. They made a model aircraft together in his studio then camped out on Perranporth airfield where he did some gliding and Matthew hung around helping out. Immediately afterwards his Dad left to go gliding in Somerset leaving Matthew feeling abandoned and acutely disappointed to be left behind. He died in hospital a few days later after his gliding accident, on the last day of August.

After a short interval Matthew started at Bryanston private school in Dorset where he did some sculpture but by Christmas he’d been re-located, following success in the entrance exam, to Humphrey Davy school in Penzance where he re-joined an important friendship group of local boys.

1965 – 1969 He won the art prize in 1968 but spent much of his time, as befits a pupil at HD, with friends more interested in science. They enjoyed making rockets and explosives, using Geiger counters to scare sun-bathing girls on the beach and becoming absorbed in local industrial history and landscape. His form teacher Mr Quixley, who was also the Geology teacher, is remembered for the extraordinarily detailed, colourful, and wondrous diagrams he drew on the blackboard which inspired Matthew to make beautiful intricate notes and drawings based on his teaching. He discovered decades later that this hero had indeed trained as an artist but then rather by accident, taken up a job opportunity as a Geology teacher.

Summers were spent working as a farm hand on his Uncle’s 300 acre farm at Godolphin House and later as a regular photographer at Lands End taking pictures of tourists at the Lands End sign post. But for many years the impact of his father’s death engulfed him; his instinct was, perhaps always had been, to avoid any sort of attention and to find ways to be left alone.

1969 Began an Honours Degree at Leicester University in Geology with Biology and Biochemistry but by year two had changed to Social Sciences, becoming seduced by Psychology:“There came a point when I really couldn’t take any more of cutting up live goldfish with scissors”

He then moved on to a frantic encounter with Archeology and Linguistics. None of it went well in the conventional sense but in some respects, liberated from family, liberated emotionally and intellectually, and somewhat surprised to find interesting people who liked him, he flourished.

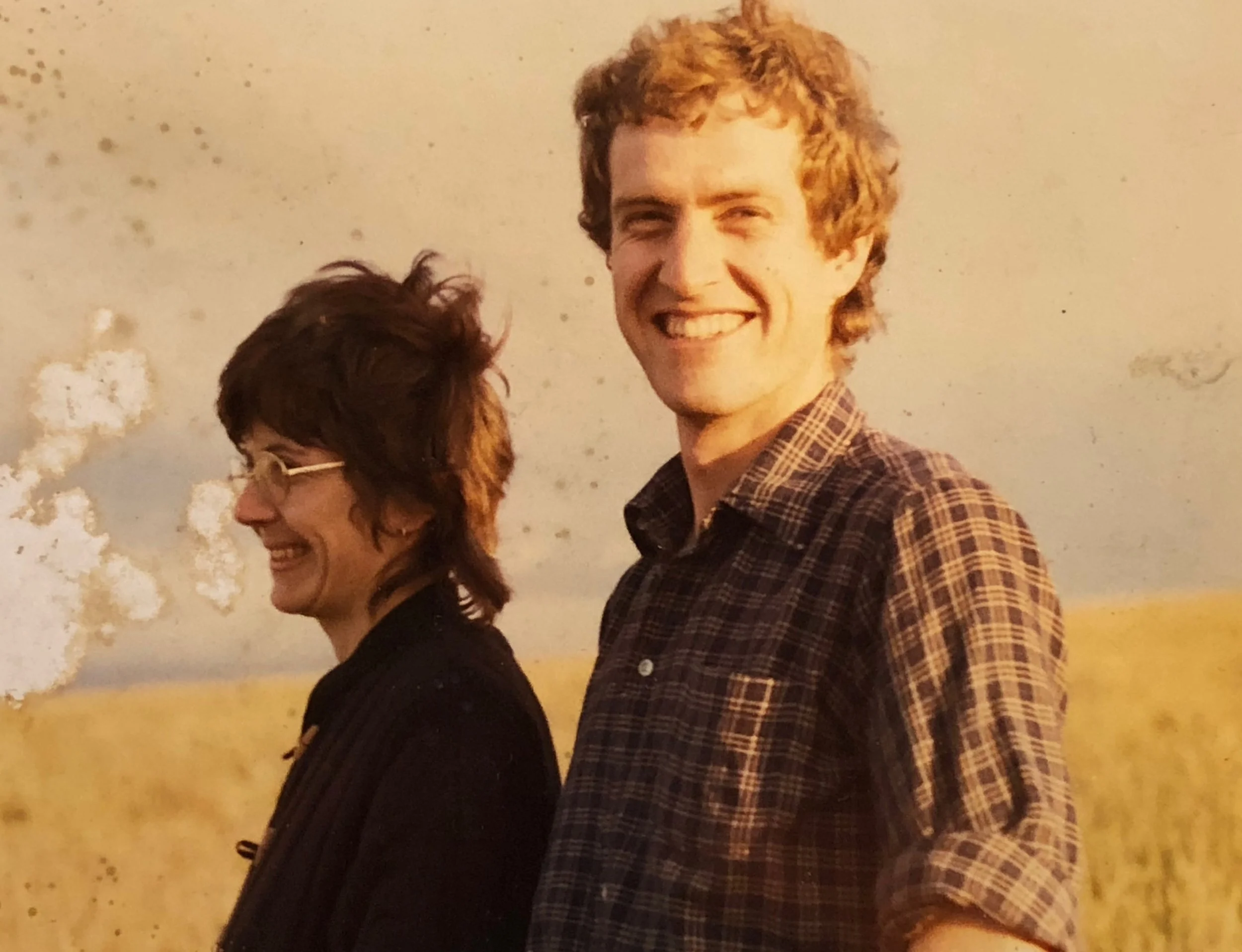

He stayed on in Leicester when his formal studies were over; travelling to Greece for long hot summers, returning to take jobs in the Walkers Crisps factory and as a postman while enjoying the company of friends whose careers were taking off astronomically in the city’s academic institutions and in the wider world of media and politics.1976 Matthew met Suzanne Brown, a teacher, and their relationship continued until her death in 2007. After travelling extensively in India in 1977 they trained together for the building trade and worked renovating houses in Leicestershire and elsewhere, as well as buying and selling household, agricultural and architectural antiques on market stalls.

1986 They moved to Cornwall with their baby son Arthur. Matthew specialised in purpose-made joinery and could turn his hand to most things including Cornish hedge building. He renovated a granite barn they were to live in in West Penwith. This gargantuan task was undertaken in the main without mechanical equipment or paid help over a number of lean years, and took its toll.

1988 to 1998 There came a defining moment when he noticed at the age of 37, on hearing a familiar engine coming down the lane, that he was hiding the evidence of his art work, even though at the time he was simply drawing at the kitchen table. It would be inaccurate to say that he did no art between school and 1988 – he was always making something; small drawings on letters to friends, re-working found objects into ‘household gods’ but the covert warning at an early age, not to entertain any notion that there might be room for him as an artist in the family, had been effective.

Inhibitions and impulses suddenly thrown into consciousness, Matthew began to practice openly and with intent as an artist. He ceased regular work in the building trade and focussed on creating three dimensional objects and images often linked to the tools of his former trades, or the realities of daily life spent tending boys, girls, goats, dogs, cats, hens and vegetables. He re-made his own tools, objects found in skips and on local beaches and also things he had bought such as old typewriters and clocks. He allowed himself to expand into areas which interested him.For these ten years he took photographs, staged and filmed brief one off moments of collision, catastrophe and revelation, wrote poems, made the occasional framed picture and created a mental and physical space into which he could expand and diversify as an artist. He discovered that his ideas came in floods and showed no signs of abating.

1995 Matthew decided to print an image he had made onto a bone china plate. It was a scene set in Mounts Bay in West Cornwall. At the time local people were incensed about off shore fishing injustices. Cornish fishermen had joined with the Canadians to thwart Spanish fleets and flags flew up and down the coast. Matthew’s depiction of two fish caught on the horns of a bull ridden by men (in what he thought were Spanish outfits but later turned out to be clothes worn by men from the Carmargue in France), was oddly surreal and satirical. It attracted some national publicity and a few sales and has been in the permanent collection at the Penlee Museum in Penzance since 1998 as a marker of that episode in local history.

1998 It was probably 1998 when he sold his first picture. He had produced a small book of images from the Bible with amusing captions, Striking Poses, (1997), which attracted a visit to his studio from a London collector who wanted several and also bought two paintings. Previous encounters with the art world had been fruitless. He had been proposed as a member of the Newlyn Society of Artists by a friend and resoundingly rejected, perhaps hardening his natural wariness of the non-commercial art world. He has been heard to proclaim: ‘I don’t teach, I don’t join societies or enter competitions or apply for grants. It has saved me an enormous amount of time.’ 1998 was also when he had his first Exhibition – a solo show of Objects and Mixed Media – at the Rainy Day Gallery in Penzance run by Martin Val Baker. It was his support and the encouragement of Matthew’s friend the local artist Rod Walker that meant he was finally able to show his 10 years’ work. He sold just one piece, to local friends, took home £75 and shouldered the burden of the £400 it had cost him to frame the show for several more years. However afterwards undeterred he created a new larger work space where he could at last get away from the dust of his joinery workshop. The effect was dramatic.

Most of the hybrid objects from those ten years still sit cobwebbed and crowded on shelves in the workshop where he now frames his own work every year: for example Torch for Finding Goats in the Dark, Annunciation - Hammer and Saw, Game for One ‘n’ All. They are relics of a time when the smallest things, whether poems or objects, took forever to consider and shape. There were moments of illumination but eventually he heard a hollow ring; was he merely a performer of trickery and self satire who would never perform, and these objects his props? He began to experience considerable mental turmoil trying to both deal with the relentless flood of his ideas and to make sense of his own work.

2001 A long poem, ‘Only Joy’ marked the end of that period. It answered the question: he was not a trickster, he was a visual artist. ‘Only Joy’ also became the overall title and was the impetus for a series (edition of 35) of five small books of poems, colour photographs and drawings which he eventually completed using early versions of desk top publishing at home. These were never shown but ‘Only Joy’ was later to form the basis of his first Bottles series of the same name. One of the illustrations he used for the original poem was a photograph he had set up of sixteen 19th century homeopathic medicine bottles filled with coloured pills, picked up from a car boot sale. He re-labelled them with a list from the poem describing elements of time – ‘fine mornings’, ‘months of Sundays’, ‘twinklings of an eye’... Framed 3D versions were eventually made available in a numbered series of uniques as Only Joy. Matthew held annual solo shows at the Rainy Day up until the closure of the gallery more than ten years later, and eventually became its best-selling artist.

In support of Suzanne’s project to produce and market her own educational resources for children he was also working extensively on small illustrations, copying classical Egyptian art. For Matthew this closely focussed encounter with exquisite line work, which had been repeated and refined over millennia, was instructive and revelatory.2005 Invited for a solo show in York,the family travelled for the launch and experienced a rare feeling of success and celebrity as two paintings were sold. This was Matthew’s first solo show outside Cornwall and the start of a relationship with David and Dee Durham who later moved to Cornwall themselves to set up The Porthminster Gallery in St Ives where they have continued to successfully promote and show Matthew’s work.That summer he and Suzanne were married; she had been fighting an aggressive cancer for several years and her intense involvement in psychoanalysis during this period drew Matthew into a process of recognising his own habits, judgements and strengths as he verbally and vicariously travelled with her. He reflects that it was a more joyful period than might be imagined but when she finally died in early 2007 he was physically and emotionally exhausted, and again struck hard with grief. Through all of it he had continued to paint with urgency and now worked largely undisturbed and alone as the demands on his time fell away.

2007 Between Feb and May Matthew had a painting included in the Art Now Cornwall exhibition at Tate St Ives which featured 28 artists currently living and working in Cornwall and in the catalogue it is written ‘in the last five years he has made 250 paintings....’ In his solo at the Rainy Day Gallery in the autumn of that year large numbers of friends and well wishers turned out in support as they had often done before and since, and his mother, supportive of his shows, was not the only person to buy a painting on opening night. In this turbulent year he had managed to produce an astonishing range of emotionally charged material. One such piece was Big Medicine - a development to a large scale of his homeopathic pills work. Each bottle was labelled uniquely in his own tiny handwriting with plurals, ‘near Mrs’, ‘clearings in a wood’, as if they were remedies. This was language as remedy, a foil to time and extinction. The need for remedies had become very real and this poignant piece used words held precious, as well as the terrible comedy of not being immortal after all.

2008 to 2014 Matthew has worked towards September solo shows in which his year’s work has been exhibited in local galleries, with work also exhibited further afield and individual collectors showing sustained interest in acquiring his paintings.

His output has been described as ‘a galloping roar’ in these years, and ‘like animals, as at home with themselves as he increasingly appears to be, and filled with the majesty of their own territories. The range is from exquisitely beautiful and intricate small works through to highly desirable large, bold paintings, as well as complex pieces beyond the usual domestic scale and rarely seen in commercial galleries’. He describes the process of painting as being on or in a big wheel that turns very slowly. Once it starts he says he is just trying to get out of the painting, finish it to satisfaction but it doesn’t always feel as though it is his own judgement at work, though it is no-one else’s.Horse imagery has figured strongly in these years in Matthew’s paintings: White Horse,White Horse to Conder Green, Blue Horse, Godrevy Girl, and Armboth Fell among others. The horse is a fictional character in the renewed relationship he has with Judith Hodgkinson with whom he has lived for some years. Judith has written about Matthew’s work (see website: ‘about paintings’ 2011, ’12, ’13.) and is closely involved in the world from which it springs: many paintings express their love: Great Western, Cinderella and the King of Cornwall, Goldilocks Zone, Big Top, Girl on the Moss, Held in Place, Pull-me-to-you, Holding the Very and If I Had a Boat.

But there are also indications of a greater pull towards St Ives after an alienation he experienced for several decades, paintings such as Baileys Lane, Cheek by Jowl, Downalong Daddyo, X Ray St Ives, and Place in the Sun reveal elusive figures in dynamic holding relationships with St Ives and its legacy. Downalong Daddyo (2013) is an explicit homage to one of his father’s small drawings ‘St Ives Harbour’(1946), carefully enlarged to scale. He continues to explore with care, admiration and a sense of fun the exciting spaces of his father’s work and what pours out of him is perhaps a muscular, highly personal explosion of what has gone in. In 2014 he lit the fuse to another large piece, Cat’sCradle, from a small pencil drawing of his father’s.

His work is unlikely to be described as whimsical now: landmass, landmarks, female figures, deep space, wrecked ships and familiar coastlines; his own iconography has continued to develop and sometimes sheds a skin if named too clearly. He continues to hold his cards quite close but can also speak very openly about the complex way in which he brings different times, places and imaginary tropes into one space and about the intimacy inherent in each painting.

The sinking of the Costa Concordia cruise ship in January 2012 began an extraordinary painting. The event is just one of the key elements in Tipping Point, at 22 feet wide, and vivid with colour, sensuality, intrigue and action, this painting is as much about human invention and co-operation, as unspeakable acts. His alternative title was ‘The Unspeakable Buttons of Captain Schettino’ and the Captain’s twisted face dominates at one end, but the ship is potentially being raised up from the ocean and while this painting deals with personal vanity it also reverberates with the need for this world to come to its senses. There appears to be a vast female figure reclining in a hammock across the canvas, and on the left is a queen, resourcefully bearing aloft her tray of hearts.

There seems too to be a new presence behind some of the pictures he makes now, hands coming round to hold from some other side? He doesn’t know yet whether these are the hands of ‘the artist’ or some ancestor- god that we’re going to need to hold things together.

He continues to expand formats; works on paper for example and a series of new prints using traditional highly skilled silk screen techniques. He is increasingly using silk screen printing in his larger works and has begun to use acrylics in addition to oils, often in the same paintings. He is also finding it liberating to use a drawing app for tablets in preparatory work.

Talking Horse (2011) is a painting on three large pieces of glass placed together. It was selected to hang in the airport at Land’s End in 2012. It features the horse, and the lovers in their wobbly cart with one wheel slightly smaller than the other, trapped on a circular journey. An elaborate image of St Michaels Mount lurks along the bottom of the painting..